Plans, Productions, and Perceptions

As nonlinear pedagogies like the constraints-led approach begin to mature, they face predictable, but important questions. CLA may be fine for “simple”, local movements usually classed as “technical” abilities, but can it scale up to the level of tactics? This question is to be expected, since it is roughly the sport version of a common question asked of ecological psychology. Invariably, a clip of Guardiola or some other successful professional coach running a session with lots of verbal instruction, mannequins, and passing patterns is presented as evidence that, in the rarified air of professional football, constraints just can’t reach the level of sophistication needed to produce underlapping fullbacks and third man runs. At this level, it is claimed, the game is something of a grandmaster chess match - a battle of blueprint brilliance in which tactical masterminds deploy orders to the foot-soldiers below.

Note: I will use blueprint and game plan interchangeably in reference to any type of model which pre-exists its context of usage.

The veneration of planning reaches far beyond the pitch, as anthropologist Tim Ingold shows in a discussion of “production” in Being Alive

Engels argued that the works of humans differ fundamentally from those of other animals, in so far as the former are driven by an ‘aim laid down in advance’ (Engels 1934: 34). True, human activities are not alone in having significant environmental consequences; moreover the great majority of these consequences, as Engels was the first to admit, are unintended or unforeseen. Nevertheless, returning to the theme in an essay on ‘The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man’, written around the same time, Engels was convinced that the measure of man’s humanity lay in the extent to which things could be contrived to go according to plan. ‘The further removed men are from animals’, he declared, ‘the more their effect on nature assumes the character of premeditated, planned action directed towards definite, preconceived ends’ (ibid.: 178). (2011, p. 4).

We see this in football whenever a manager first considers if the execution of actions conformed to the game plan, and only second, considers the outcome of the game. A win may be achieved in multiple ways, but none better than the one which conforms exactly to the predetermined plan. A certain honour is assigned to ‘sticking to the plan” and eschewing momentarily pragmatic solutions which deviate from it. The game played on the field should flow downstream from the game plan set beforehand. Beautiful football originates in the mind of a brilliant manager who arranges his or her eleven players in some magical and novel array.

Despite the fact that the above narrative all but monopolises the football discourse, it stands on tenuous philosophical ground which it inherits from its pre-sport ancestry. Most obviously, if we trace this blueprint → game relationship back we are stuck positing a blueprint or game plan that came before the first actions of the game were ever made. How could a manager of a sport that has never been played exist, let alone create a game plan? If we accept that at least some form of the game must have been played before managers and game plans, they lose their position as causal determiners and become, at best, intertwined with gameplay.

A further issue becomes apparent when we consider the relationship of the game plan, or really any form of instruction, to the actions which unfold in reality. Let’s think of the video game FIFA for a moment. The user controls the movements of the player, but only within a certain range. For example, I can direct the player to run forward, but I don’t have to tell them to put one foot in front of the other, touch the ball, and so on. Of course there are always various attempts to add in some manually controlled skill moves, but suffice it to say there is always some portion of the player’s movement which is handled by the computer.

Consider, also, a frustrated manager being interviewed after losing on what is deemed to be an “individual error” - a player misplacing a ten-yard pass, or mis-controlling a simple touch. This is “beneath” the manager’s level of responsibility, it is understood.The game plan may have been correct but an error in its execution was to blame. This level of play is expected to be ready-to-hand (in Heideggerian terms) to the manager as they construct their game plan.

Even the most detailed of game plans necessarily under-specify the actions of the players on the field. Consider the ridiculous thought of a manager telling a player to put one foot in front of the other, inhale, exhale, and so on. It should be clear now that all game plans are frame-works or heuristics and leave something to be “filled in” during action. We might think of them as classes of scenarios in which actions should be executed. Remember, the “raw” action such as playing a pass with the inside of the foot is considered to be the responsibility of the player. It is the “higher level” guidance such as “switch it to the weak-side winger who then gets to the endline and cuts it back” which is the domain of the coach and his or her game plan.

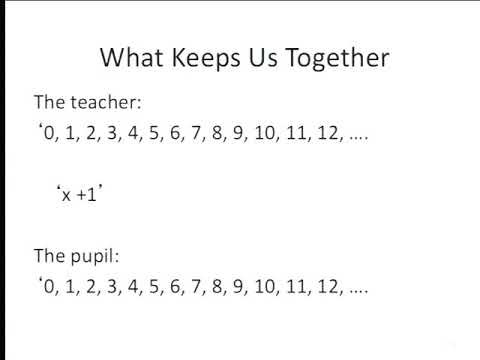

As we have established, however, the above instruction (and this is true of all instruction) does not completely specify the conditions of its own application. It is a sort of vague heuristic. It leaves unspecified the precise manner in which this should be executed, but it also cannot tell the players exactly which class of scenarios it applies to. Anyone who has dealt with young children has dealt with this sort of questioning. “What if the house is burning down? Would I still have to clean my room then?” and so on. We can play a similar game with the manager’s instruction here. What if the player in possession is in front of an empty net? Should they forgo the goal to follow the instruction? The answer to such questions is always an exasperated appeal to common sense.

Wittgenstein on the (im)possibility of rules “keeping us together”

But what is common sense in this case other than the player’s action-perception of the affordances of the environment? It has already been established that this type of functioning is necessary to “fill in” the gaps in the framework, but rather than being confined to this “lower” level the player’s real-time perception of affordances is also called on to decide whether the game plan’s under-specified conditions of application have been met. Every manager in the world expects the player to put the ball into an empty net rather than pulling it back and finding the winger. If this is not convincing, consider the player’s instantaneous recognition that whatever game plan they had no longer applied the moment Christian Erikson collapsed on the field in the recent Euros. No one expects the manager to add “but if a player has a heart attack you don’t need to switch the ball.”

Those familiar with motor control will, of course, understand the issues with assigning hierarchical status to tasks based on their appearance of “cognitive complexity”, but we will retain this framing in order to meet the discourse where it is. We have shown that action and perception are necessary to animate the so-called lower level details of the plan, but most importantly, that they are also needed at a level which transcends the very game plan itself! The position of the game plan is sandwiched between the ability of the players on the pitch to act and perceive “live” information, not pre-set game plans.

So if game plans must rely on action-perception both “above and below” why are they deemed necessary in the middle? Are advanced football tactics really too complex and “heady” to be taught with a constraints-led approach? Is there some point at which players can no longer adapt to the demands of the game using their real-time action-perception capabilities and must switch to verbal instructions, rules, and heuristics?

The answer can be found in the way pre-formationist (blueprint) thinking pervades the whole developmental process. The professional adult game is seen as the consumer in the production of youth players. The pro game places orders for academies to fill. The endpoint of a player’s development is thought to exist before it even starts. As we did with managers, we must try to imagine a professional club that existed before the game was ever played to see how ridiculous this is. The outcome of this is a type of path dependence that may be locally optimal but can be shown to be globally inefficient.

The basic set-up is as follows: Development should give players a “technical foundation” which will later be the raw or lower-level actions which fill in the gaps in the higher-level game-plan. Since these actions are intended to be automatic machine-like motions given direction by a plan, there is no need for them to be learned in any specific context. The result is often players who have trained in impoverished environments for much of their development and fully expect the “tactical” or decision-making portion of the game to be handled by the manager.

Consider the following metaphor. You would like to bake bread - specifically whole-wheat bread. You go to the store and see only white, bleached flour. The health food aisle, however, carries wheat germ and wheat bran. You buy these and mix them back in. In some instances this might be the quickest way to create whole-wheat bread. It should be obvious however, that it is not a globally optimal solution since it assumes the process of removing what is later added back in. This, I argue, is what is behind the claim that professional managers can’t do without explicit instruction at the tactical level.

Of course, players are never really the equivalent of bleached flour, since there is no such thing as a context-less skill. Even the control of a short pass involves a tremendous amount of decision making. A first touch isn’t just the interception of a moving object with the body, it is the attempt to guide that object in a manner which maintains an “optimal grip” on a field of affordances. The technical-tactical narrative has trouble explaining such abilities. Talk of instincts, game intelligence, or natural talent usually fill in this gap. A much more elegant explanation of these supra-technical abilities is to consider them as outcomes of information-rich developmental contexts. This is precisely the position that the mythology of “street soccer” occupies in popular discourse. It’s not about playing on asphalt as much as it is a recognition of some unexplainable surplus to the technical-tactical narrative.

In conclusion, we should ask not whether CLA is capable of scaling up to the level of advanced tactics, but why this artificial niche has been created in the game. If the player’s action-perception capabilities are needed to determine the conditions of application for a game plan, (if we follow the hierarchical logic this must be above the game plan) then they are certainly sufficient to perceive those elements of the game labeled as tactical. This is the case even within a developmental system that has done all it can to “bleach the flour”, or isolate movements from contexts and decisions. There is no telling how much more easily a generation of players raised without these aspects ever having been separated will be able to perceive tactics. This is similar, I think, to times in history in which it was assumed that literacy was not accessible to the common person precisely because they were denied access to written materials. Reading the game is for everyone.

References:

Ingold, T. (2011). Being alive essays on movement, knowledge and description. Routledge.